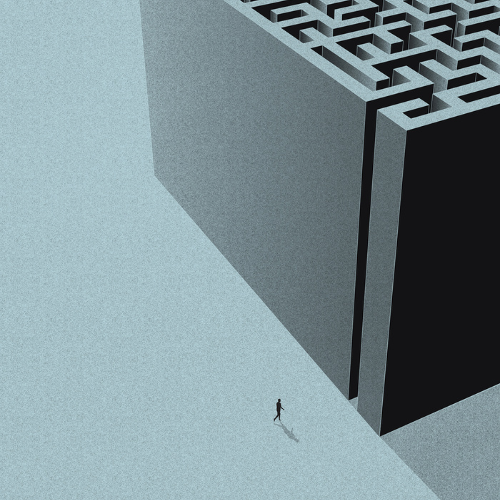

Part 4 "The Newton Phase"

I call this my “Newton phase” — because everything I built seemed to have an equal, opposite, miserable, or greater outcome.

During this time, I survived again on side hustles, reinvested everything into building ideas, and even worked as a door-to-door salesman — pitching the idea before the product even existed. I learned an important lesson (the hard way): getting users before the solution is built is powerful, but it doesn’t guarantee success just because people say “yes” once.

One of my biggest experiments was an inter-city and inter-state e-commerce platform:

The vision, you could buy from your local city stores right from your home, but also order from shops across other cities in your state.

The result? Failed — big time.

Why? Because it was almost impossible to convince shop owners to handle the headaches of e-commerce: shipping, returns, and still keeping prices competitive. I had onboarded 50+ wholesalers and retailers, all of whom paid registration fees, which boosted my confidence. But when operations started, it collapsed. No one but me to blame here, I sold them the idea but not the practicality of it, which even I was unaware of at the time.

But this failure introduced me to three things: extreme resilience, a deep dive into human psychology (because if you’re selling or building for humans, you must understand them first), and what I call “The Hard Scale Theory.”

What is that? Simple:

Get 50 people, explain your plan, and ask them why they wouldn’t use it. Take notes.

Example: “Here’s a pen. Here are all its features. Now tell me at least 10 reasons you wouldn’t use this pen.”

I was Doing It All Wrong: Sitting down and trying to think of ideas for other people’s problems is a big mistake. For me, the real approach is to look at the problems I face every day—the ones I’m tired of, the ones I desperately need solutions for. From there, you’ll discover a set of serious issues. Then, see which of those problems are shared by others at scale, problems that will only grow worse over time. In the end, you’ll find one or two things that both you and others desperately need solved.

You must be both the scientist and the lab animal in your own experiment—because if you’re not living that problem daily, how can you possibly find the best way to solve it